Why I Write

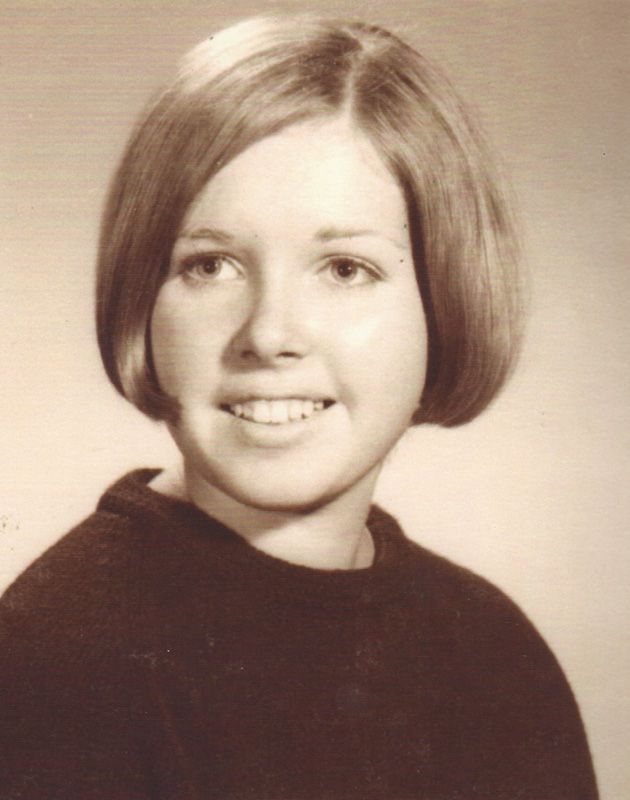

/Photograph by Karen Thompson

Throughout my career I’ve written for the trend, for the times, for the zeitgeist. I spent years in the public relations/marketing profession, where being current was currency, and built a reputation as someone known for “getting it.” So I was surprised when I encountered push back over the years as I wrote my first novel, set during the Vietnam War, as to why anyone would be interested in the subject matter. It’s over. It’s been done. Why should I care? I wasn’t around then. It’s irrelevant to me, to today.

Such comments always made me respond with a crack referencing the latest hit movie set during World War II, about a war that took place before most of us were “around,” and yet endlessly of interest, of relevance.

This millennial resistance to all but the immediate present has caused me to think a great deal about the notion of relevance. The concept seems obvious as I work on a second novel about the experiences of two women in Germany during the Great War, and how what they went through trickled down to profoundly harm their children, and children’s children. These influences may have begun yesterday but highly impact today and, as more children are born, without question, tomorrow. In fact, the point of the novel is to wonder how very long, into how many generations, the impact of war can last.

I think of relevance as I work on a memoir in essays about my own life that highly resists staying in the present, or even in my own past—it circles back, farther and farther, into the influences of those that influenced me.

My own present has many dimensions that began long ago. It’s hard not to feel it when my physical therapist helps me stretch out the impact of the gymnastics incident that threw out my back when I was sixteen; the car accident at thirty that messed up my neck, gave me a lifetime of migraines and threw me permanently out of alignment; and the mugging at forty-something that saved my purse but frayed my rotator cuff. Our bodies are like old cars, I believe, the injuries of our past dinging us with every morning wake up.

So too, are our minds and our memories. What else explains the need for so many therapists who help us deal with patterns, fears and behaviors that belonged to generations long ago and have been passed down, unwittingly, to influence and inhibit how we deal with achievement, relationships and what we in turn pass on ourselves?

With every throb of the little finger of my right hand that reacts when my back goes out or pang of head pain that comes with the low barometric pressure of summer storms, I go back to the source, and am reminded where this all started.

I’ve always told my clients, in my most recent profession as a career consultant, to stop and reevaluate as they progressed. You’ve worked for twenty years, I’d say, thirty. What is the combined value of that experience, expertise and point of view? That’s what you are now. It’s what makes you unique and is the foundation of the legacy you leave for others.

And so it is with history. We are informed way beyond the shortsightedness of the present.

Viet Thanh Nguyen was nominated for the National Book Award for Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War. President Obama quoted William Faulkner about how “the past isn’t dead. It isn’t even past.” The past, immediate or far, what happened to others, the country, the family, is all there when you crook your little finger. It’s what made it happen. It’s why it still happens.

Physical, mental, familial, historical. We are the ancestry.com of our times and to continue to move forward there’s an imperative to connect the dots, to identify the patterns, to factor in everything, to acknowledge.

Nothing is irrelevant.

This is why I write.