Women’s History Month: A Matter of Standing

/Women’s History Month isn’t an anniversary I typically celebrate or to which I pay much attention. Early in my career, in fact, like so many of us, I worked hard not to differentiate. Making an issue of being a woman in the workplace seemed to underline the very differences I was trying to equate. However, as I type this, I admit to feeling ashamed of myself and that—though I’m dying to meet Gloria Steinem in real life—I hope she doesn’t inquire about the details of my feminist record. It’s there, but in my younger years I did work harder for what seemed more immediate, achievable goals, like ending the Vietnam War. I would say I don’t feel tragically ashamed, more like the descendant of a suffragette being admonished by her ancestors: “Do you realize what we went through?” I’ve always been on the right side—but not raging. I wanted my career and achievements to speak for, not themselves, but for me. I had earned that standing, regardless of gender, I felt. Looking back, after learning how hard it was to be heard, even when you did everything right—even way beyond right—I wonder what on earth I was thinking about. Why did I feel I had to prove anything?

Standing: That Which Is Assumed for Others Often Needs to Be Earned or Proven for Women

Lori Lightfoot (right) and Toni Preckwinkle, run-off candidates for mayor of Chicago

Shame is certainly not the word I apply to this past year. This is a shout-it-from-the-rooftops time. From the speak-up success of #MeToo to the feminism of Congress (I love saying that) to the fact that in my city of Chicago, we are going to have an African-American woman as mayor. She might even be a lesbian. Those aren’t the reasons I’d vote for a mayor, but it’s all pretty cool to see that the field is feminine, so the choice is gender neutral. I’m hoping the campaign will be civil and issues-oriented. The road is rocky ahead, as we can already see from snide comments about these remarkable women. Yet, to be standing tall on this road is significant.

The Issue Is Long-Standing

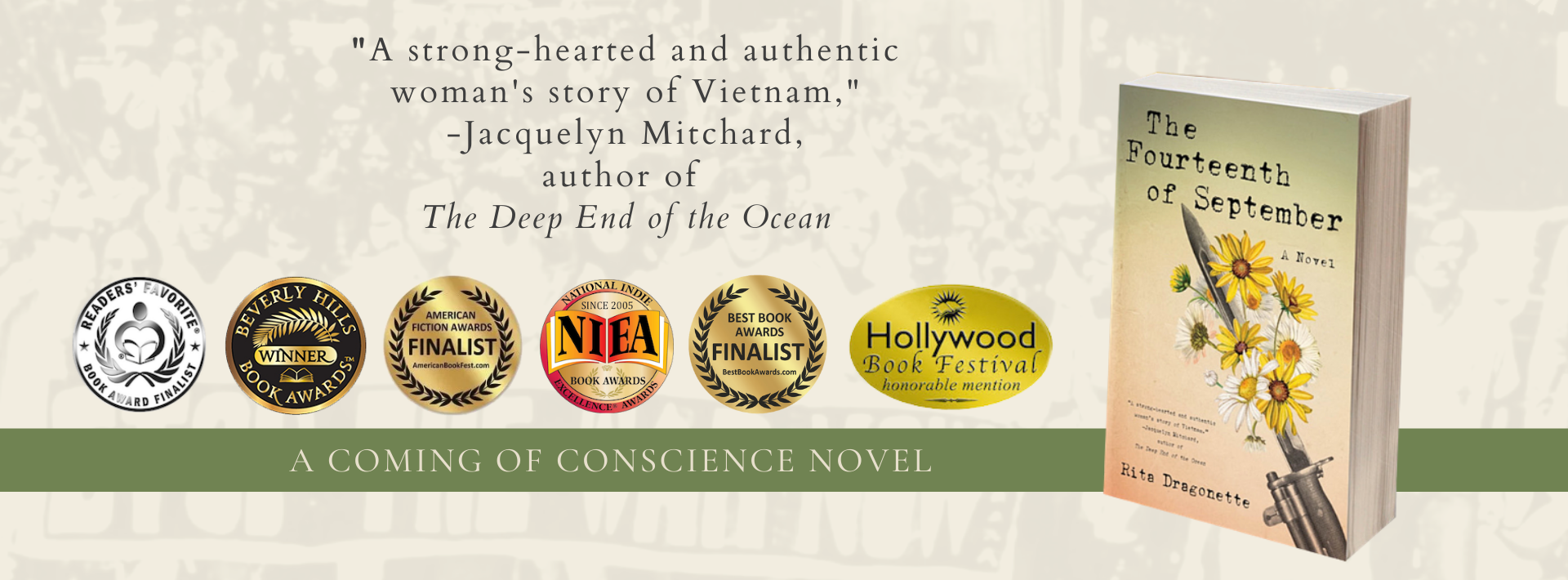

The extraordinary and hard-earned events of the year aren’t, however, why the standing of women has been on my mind. I launched a novel in the fall, The Fourteenth of September, a woman’s story of Vietnam. I’ve been talking about it across the country and answering continuing questions about why I would write a book about that war from a woman’s point of view: What was my intention? Why would it matter? How could there be a story if women weren’t even in the war? Their lives weren’t on the line, were they? These aren’t judgmental questions, they come from a point of genuine curiosity, and an eventual thrill that there even is a story about women during that war.

The discussions have been like peeling an onion. The first comments are usually from men, sharing their experiences of the Draft Lottery, but then, slowly but surely, the women’s questions begin. They have stories of experiences as well—of impact, not combat. As the queries deepen, so do my answers, and I find myself going back to my childhood where issues of inequity began for so many of us. Mine was a bit unusual, so the disconnect was clearer.

Both my parents were in World War II. My mother actually saw much more action than my father (I’ve always loved saying that). She was a nurse, a first lieutenant, overseas for three years. My father was sent to Panama, out of the war, and came to Europe after D-Day but in time for the Battle of the Bulge. I don’t want to compare their experiences and assess which one had it worse, since that will undermine my whole point, but the details are significant to set up the issue.

Edith Finnemann Hoey, 1st Lt., Army Nurse Corps

My mother had stories (and scrapbooks) that we pried out of her years later that were amazing: in Patton’s army, helping perform meatball surgery in twenty-hour shifts in a tent on the front, dipping her cup into a tub of cold coffee to keep awake before rotating behind the lines for a little rest before it would start all over again; part of a team on VE day that liberated Stalag 11 in Heidenheim, Germany. As the daughter of Danish immigrants she could understand German, and when the captured men smiled and called the Americans names—just like in the movies—she giggled that she could wait for the killer moment, then answer back in their own language, showing she had understood all along, stunning them that this twenty-six-year-old farm girl could smack them back in place. It was cold in Heidenheim, and the prisoners had little clothing. They were huddled in the fetal position to keep warm . . . for years. Her job, as head of triage, was to take their limbs and try to pull them apart to see if there was any range of motion, any hope for life. Just take a moment to imagine what that would be like. But she didn’t want to talk about it. Not, we thought, because most vets didn’t, but because she had found that “no one wanted to hear it.”

When conversations began, she was usually shut down with “but you were just a nurse.” It was my father who was the sanctioned target of a bullet that could kill him, so his stories were the real war stories. My mother didn’t have the necessary standing to be taken as seriously, so she went silent. Eventually she began to agree—maybe what she’d been through hadn’t been that important after all. Maybe her contribution hadn’t been that significant.

Even as a child I remember thinking it so odd that the war experiences of my parents would be assessed and weighed differently. It didn’t make sense. They were equally brave and patriotic. What they went through was equally dangerous and horrific. Why would a scale be applied? Though my mother’s life could also have been lost, it wasn’t technically on the line. She didn’t have standing. Therefore, she didn’t have respect. And yet, though I could imagine my father shooting someone, I couldn’t picture him having the patience and compassion to slowly coax frozen limbs away from bony rib cages and out into the light.

Do We Need Standing for Respect?

When it came to Vietnam, the war of my generation, I was surprised to see similar circumstances happen firsthand. In the antiwar movement, where so many women were involved, despite early feminism it was often very hard to be taken seriously. In the depths of the terror over the Draft Lottery, you could participate, organize, empathize, comfort, but—as you could be told in a snap—you could never really understand what the guys were going through because you would never face a bullet or wonder if you could kill someone. We were often marginalized, just at the point when we felt we were breaking through with our own contributions. We didn’t have the standing to be taken seriously.

The Fourteenth of September is a story of those women. My intention was to pose a female dilemma with the same gravitas and emotional intensity as the decision the men had to make about going to Vietnam to die or to Canada, another kind of death. I call it a Coming of Conscience novel. I wanted to explore how a woman would approach the decision of integrity trumping consequences, how she’d weigh the same factors of duty, security, future, and conscience. It’s as close as I could come. I wanted to give my character Judy the standing she deserved, and, I suppose, however little and late, my mother.

Before my mother died, she talked about how disappointed she was. She’d felt her daughters would fare so much better without the many restrictions of her time. Though there’d been a lot of change, she thought that in her long ninety-year lifetime, we’d have settled this issue of standing.

Standing Tall

My mother has been gone for over a decade but would have been gratified about the achievements of women in this year, celebrated in this Women’s History Month. We’re far from settled, but we are certainly standing taller and perhaps, at some point, we’ll naturally loom so large we won’t have to think of it at all. And someday Women’s History will just be History.

In the interim, I won’t let it pass. I’ve scheduled posts and Facebook ads on the issues I’m writing about, and I’m celebrating. Today, I totally assume standing for my story, for my “record,” and I’m standing up—just like Mom.

My mother, sometime in the 1940’s, standing tall and fearless. I have no doubt she’d pull that trigger.

![momWWII%20photo[1].jpeg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/581992a5f7e0abdf04947525/1535419574442-WOB1100C6U3RM5DXOMY0/momWWII%2520photo%5B1%5D.jpeg)