The Final 50th Anniversary Post: Remembering the Kent State Shootings of May 4, 1970

/On this date in the year 2070, someone will be writing about how the Great Coronavirus Pandemic of fifty years earlier changed the world and why we are better off for it in some ways, worse off in others, and how mystifying it is that there are still those lingering issues that haven’t yet been settled. And, isn’t it about time we finished the job and stopped repeating history?

Anniversaries are important to make sure we ask those questions. It’s why, over the past two years, I’ve written posts about the anniversaries of so many events that shaped the world during the time frame of my novel The Fourteenth of September and still resonate today: the Bobby Kennedy Assassination, the 1968 Democratic Convention, the Moratoriums to End the War in Vietnam: October 15, 1969 & November 15, 1969, the First Draft Lottery and the Kent State Shootings.

This will be the last anniversary post on the history behind my novel; the cycle is done. The story takes place roughly between the first Vietnam Draft Lottery and the Kent State Shootings, two seminal events that book-ended a six-month period wherein I’ve always felt the character of my generation was formed, including its early feminism. The novel ends shortly after Kent State when the country fired on its children, the turning point incident in support of the war when the country went too far and knew it.

Fifty years sounds so long, but in many ways has gone by so fast. What we haven’t learned in that time frame is legion. Just this past December, the Washington Post published a report, “At War With The Truth,” about the war in Afghanistan, that sounded like the playbook for Vietnam: falsified data to show we were “winning,” admissions that the strategy wasn’t working, and the objective unclear. On the positive side, we learned to treat our vets with respect, to never have another draft, and we keep coming close to electing a woman president. Two steps back, one step forward, another we just can’t seem to get quite right.

We are still so in the thick of this pandemic that, yes, it’s difficult to focus on anything else. But it’s illustrative, on today’s anniversary, to consider how we might try to learn the lessons of how to be the admirable country we consider ourselves to be, the first—or the fifth—or the fiftieth—try instead of so often falling back into the hamster wheel of history.

Following is a post I wrote on this day two years ago, that includes the story of what happened at Kent State University on May 4, 1970, and why it still matters today. In rereading it, I see that we were only thirteen months into the new administration, dealing acutely with school shootings and already hearing about alternative facts and incredible re-interpretations of reality. I asked readers to look ahead and think about what would be on the conscience of the country on this fiftieth-anniversary date to which we should also be saying “No, that’s not who we are.”

The issues have changed, but not the question. How we’re dealing with acceptable percentages of pandemic deaths and knee-jerk 180 turns in policy that impact lives and livelihoods. I ask again. Haven’t we learned how to be better than this. Are we ready again to stop and say, “No, that’s not who we are?”

Remember Kent State, May 4, 1970: An Iconic Moment For A Generation... A Coming of Conscience for a Country

Recently, while promoting the fall publication of my novel, The Fourteenth of September, which takes place during the pivotal 1969-1970 years of the Vietnam War, I was asked if—of the many iconic moments in American history that happened during that time period— one had impacted me more than any other.

I paused to consider the word iconic... icon — a symbol. No question. It was the Kent State Massacre, a symbol at the time of the total chasm between the government and the youth it was supposed to be protecting: the bridge too far that blew away most of the remaining support for the war, though it’s death throes dragged on another five years.

48 Years and We Still Remember

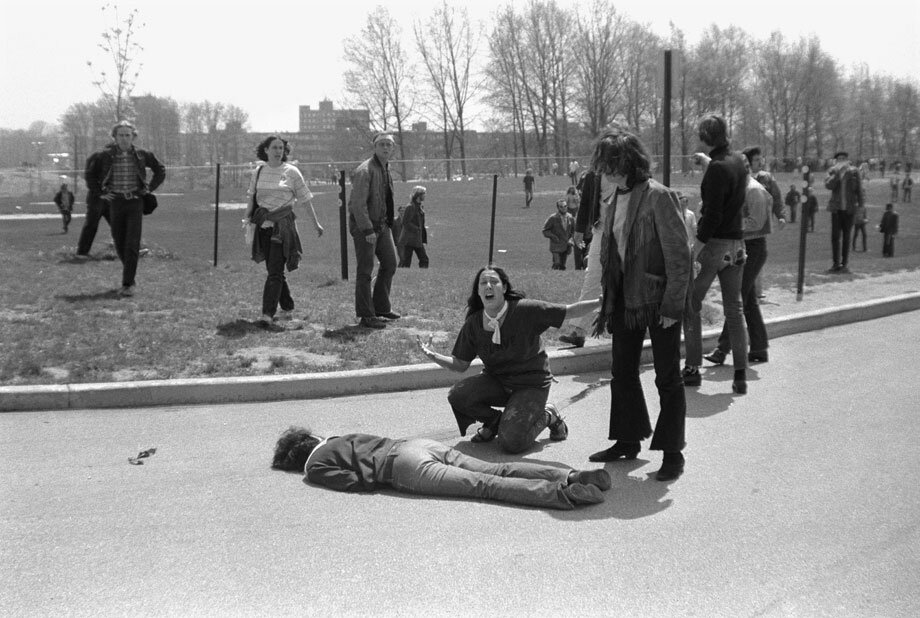

Every May fourth since 1970 there has been media coverage of the shootings, always featuring the Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph of fourteen-year-old Mary Ann Vecchio with arms outstretched in agony and disbelief, kneeling above the body of twenty-year-old Jeffrey Miller. An iconic image of how we felt. Agony and disbelief. This is America? How had it come to this?

We know the facts: The National Guard fired into a crowd of students protesting the war’s expansion into Cambodia. Sixty-seven rounds over thirteen seconds killing four, wounding nine, permanently paralyzing one. The massive national student strike after. A turning point in how the country viewed the war. It was just too much to kill kids.

Early Alternative Facts

It all began with a lie—and it was bald-faced. Nixon was elected because he said he'd end the war—something his predecessor, Johnson, hadn't been able to do. His Administration said we were winding down. Hard as it may be to believe from the vantage point of today, media was limited. We only heard one side and assumed what we were told was true—though obviously that was disavowed later on many levels, most recently in the Ken Burns documentary The Vietnam War.

But, suddenly, on April 30, 1970, it's announced we just bombed Cambodia. It was earth-shattering. The war was being accelerated, not contained. Of course, there were protests; of course, they were full of anger; of course, those protests would be on a campus where the populations of draft-age men were among the largest. We had just been through the roulette of the Draft Lottery and the news about My Lai. Nerves were raw, the rage was high. Above all, trust was waning, and this Cambodia lie just wiped it out. How could we believe anything the government told us ever again?

And then, to top it off, unbelievably, students were shot dead at one of those protests. It was the very definition of a word we were just beginning to use to describe what we thought were mind-expanding experiences: surreal.

Where Were You When You Heard?

I think many people of my generation can tell you where they were and what they were doing when they first heard about Kent State, just like all the assassinations that punctuated that time—King, the two Kennedys. I remember walking into the Student Union with a few others and being shocked to hear my friend, Tommy Aubry, screaming from the top of the stairs, “They’re Shooting Us! They’re Shooting Us!” We didn’t know what he was talking about. He pointed to the only television set in the Union and ran past us to shout the news to others.

We didn’t believe it at first. Who would? They must have shot over their heads. It had to be an accident. Surely no one was actually dead. It was too fantastic to comprehend... until we had to. The truth of it was horrible. It wasn’t enough that we could be sent to Vietnam to die; we could die here.

They Could Shoot Us, Too!

I came across a quote by the survivor, Gerald Casale, that summed up a student’s point of view. “It completely and utterly changed my life. I was a white hippie boy and then I saw exit wounds from M1 rifles out of the backs of people I knew...”

In an era of embryonic diversity awareness, it was astounding that supposedly the most cherished of us all were now being killed just outside a quiet Midwestern town. Anything could happen next. Casale founded the band Devo, creating music and a movement as a result of his experience.

I have a chapter in my book you can read here that’s based on what happened at the campus I was on. It was not something I had to research. I still remember every second.

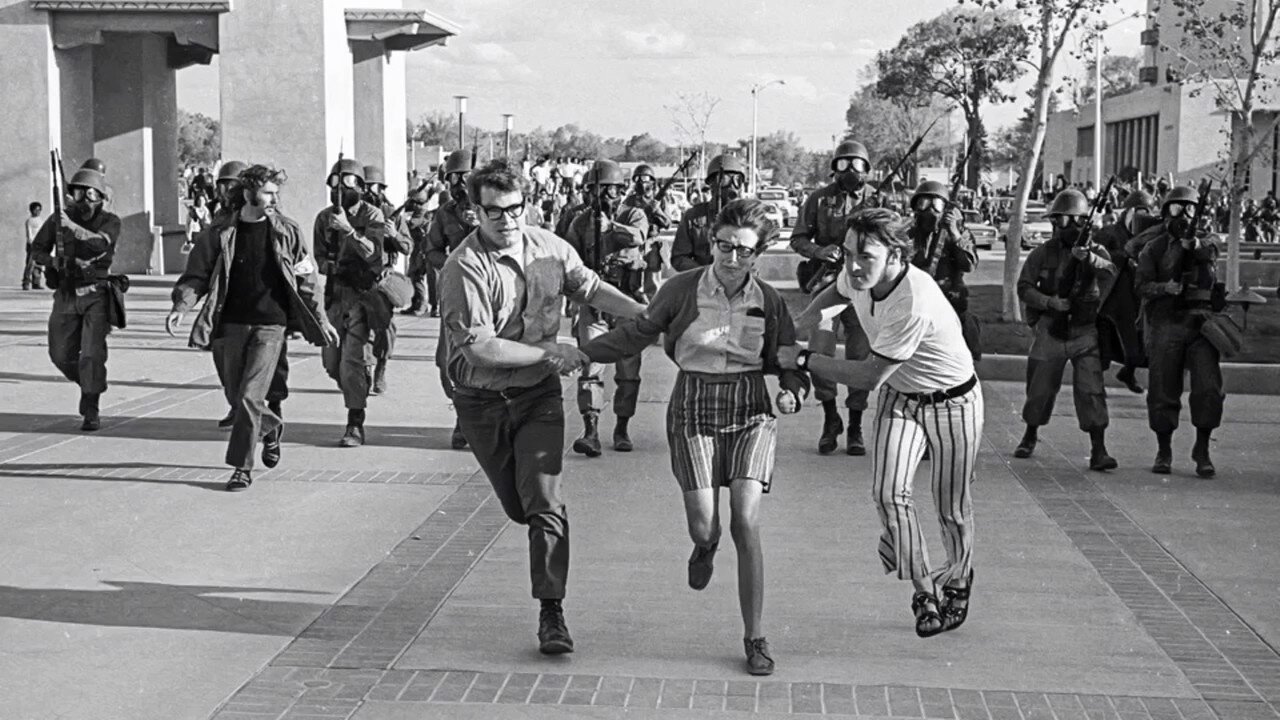

Within days after the shootings, the National Guard actually did arrive on my campus, and we thought we were also going to be killed—another chapter, another iconic situation. We were still teenagers and most of us had been pretty sheltered, but now we understood what it must be like for those fighting for civil rights in the south, for anyone living day in and day out in any country at war. It was a sobering lesson. We were truly in what we called "the war at home."

According to the final report on the Kent State Massacre by the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest: “It was unnecessary, unwarranted, inexcusable”—an iconic symbol of the war that caused it.

A Coming of Conscience Moment. America Said No!

The subtitle of my novel is “A Coming of Conscience,” because it was a time when we weren’t just growing up and Coming of Age. In addition—by the way we chose or were forced to cope with the situations presented by the Vietnam War—we were each defining our own character. We were each faced with decisions where integrity could—or should—trump consequences (pun intended). Would I go to Vietnam or to Canada? If I join ROTC (Reserve Officers' Training Corps) am I being realistic or complicit? If I put my head in the sand and try to ignore it all am I being apathetic, cowardly or just understandably self-preserving?

We’re in a period now where we’re questioning our leadership and taking our positions on matters to the streets in massive marches. It’s our right and our privilege, and they don't fire on us—we feel safe. One reason is that on May 4, 1970, the country looked aghast at the bodies of those dead children and decided that this was not who we were. This was not our character. It was a coming-of-conscience moment for the country.

It all reminds me of watching Apocalypse Now, a brilliant film that I admired greatly but could never see a second time. Viewing it made me feel I’d personally been through the war. It told the Heart-of-Darkness story of Colonel Kurtz, who embodied "the horror," as he put it, of how we would actually have to behave to win such a war. In the movie, the government has sent an assassin to eliminate him, because as a people we couldn’t accept that Krutz is what we’d have to become to do what Washington considered so essential—continue as the country that had never lost a war.

With Kent State, the horror rang through every level of America. Is this what it’s come to? We answered, “No.”

May 4, 2020, will mark the fiftieth anniversary of the massacre. Over the coming years, let’s remember and honor what happened at Kent State. And, in this current moment of dubious facts, incredible re-interpretations of truth and Never Again, let’s think of what else is on the conscience of the country to which we should also be saying, “No, that’s not who we are.”